If you make your living in and around our probate courts you’ll find the FY 2020-21 Probate Court Statistical Reference Guide interesting reading.

Probate court filings increased state-wide by approximately 50% over the last 10 years, which is more than twice Florida’s general population growth rate for this same time period. I don’t know what’s driving this spike, but I suspect it may have something to do with the disproportionate growth in Florida’s senior population.

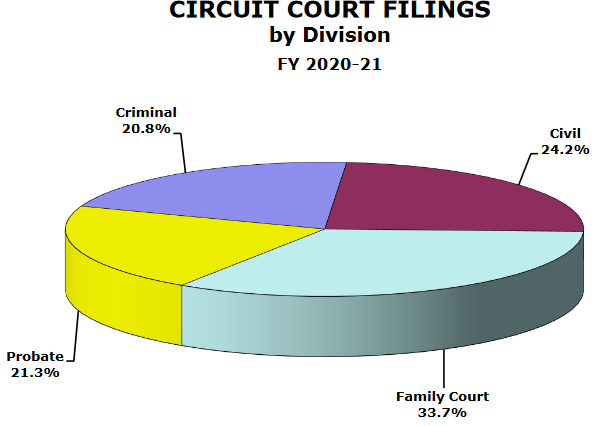

A little over 1 out of every 5 circuit court filings in Florida happen in one of our probate divisions (21.3%). That’s a lot of work for probate lawyers. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Real Property, Probate and Trust Law Section is the largest section of The Florida Bar.

By the way, it may come as a surprise to learn that only about half (49.8%) of the workload of your average probate court is dedicated to “probate” proceedings. And in some circuits it’s less than half. For example, in Broward the number of Baker Act filings (5,772) exceeded the number of probate filings (4,699). And here’s another somewhat surprising finding: “guardianship” and “trust” matters — which loom large in most practitioner conferences and publications — are a tiny sliver of the cases actually filed.

How busy are our probate judges?

This chart is my creation. The goal is to get a sense of how busy our probate judges are by taking the “cases filed” data reported in the FY 2020-21 Probate Court Statistical Reference Guide 6-4 for three of Florida’s largest circuits/counties — (Miami-Dade (11th Cir), Broward (17th Cir), and Palm Beach (15th Cir) — and dividing those figures by the total number of dedicated probate judges for each of these circuits as reported in the FY 2020-21 Overall Statistics 2-2 page.

| Type of Case | Miami-Dade (11th Cir) | Broward (17th Cir) | Palm Beach (15th Cir) |

| Probate | 5,123 | 4,699 | 5,368 |

| Baker Act | 4,634 | 5,772 | 2,744 |

| Substance Abuse | 768 | 828 | 686 |

| Other Social Cases | 2,173 | 365 | 255 |

| Guardianship | 907 | 523 | 580 |

| Trusts | 47 | 77 | 155 |

| Total FY 2020-21 | 13,652 | 12,264 | 9,788 |

| Probate Judges FY 2020-21 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Total/Judge | 3,501 | 4,088 | 3,263 |

What’s it all mean?

In Miami-Dade – on average – each probate judge took on 3,501 new cases in FY 2020-21, while in Broward the average was significantly higher at 4,088/judge, and in Palm Beach it was the lowest at 3,263/judge. Keep in mind these figures don’t take into account each probate judge’s existing case load or other administrative duties.

These caseload figures may be appropriate for uncontested proceedings, but when it comes to that small % of contested estate matters that are litigated these numbers (confirmed by personal experience) make two points glaringly clear to me.

First: “privatize” the dispute-resolution process whenever possible:

We aren’t doing our jobs as planners if we don’t anticipate — and plan accordingly for — the structural limitations inherent to an overworked and underfunded public court system. One important aspect of that kind of planning should be opting out of the public dispute-resolution system (our courts) and into a private dispute-resolution mechanism (arbitration) whenever possible. And how do you do that? Include mandatory arbitration clauses in all of your wills and trusts. These clauses are enforceable by statute in Florida. I’m a big fan of this approach (see here, here, here, here).

Here’s how the authors of the ACTEC Arbitration Task Force Report described the “structural limitations” argument for privatizing estate disputes:

What is now a choice to agree to arbitrate or to require arbitration may become a practical necessity. To have this vision one need only look to one’s own jurisdiction and the yearly budget disputes between governors and legislatures as they make difficult spending choices. The “third branch of government” is not an uncommon target. Within that debate, social and political considerations mandate that our leaders use their limited resources to fund criminal, juvenile, and family justice long before they reach estates and trusts. As judicial resources dwindle or shift to a more pressing use, it is apodictic that already slothful judicial resolutions of trust and estate litigation will slow even further. In jurisdictions with competent, up to date jurists, we see constant outsourcing of trials to retired judges and magistrates with more time on their hands. And, of course, the competent, up to date jurist will eventually retire.

Second: help our judges do the good job they want to do:

We aren’t doing our jobs as litigators if we don’t anticipate — and plan accordingly for — the “cold judge” factor; which needs to be weighed heavily every time you ask a court system designed to handle uncontested proceedings on a mass-production basis to adjudicate a complex dispute or basically rule on any technically demanding issue that can’t be disposed of in the few minutes allotted to the average court hearing.

And how do you do plan for the “cold judge” factor? Read Persuading a Cold Judge. Here’s an excerpt:

Begin at the beginning. In every court appearance, there are six basic queries to answer for a judge:

- Who are you?

- Who is with you, and whom are you representing?

- What is the controversy, in one sentence?

- Why are you here today?

- What outcome or relief do you want?

- Why should you get it?

This last query is most often forgotten. Indeed, these six essential queries are a good beginning even when you are dealing with a warm judge. Consider putting them on a PowerPoint slide, a handout in the form of an “executive summary,” or a demonstrative exhibit to project through Elmo or other presentation technology.

A judge in a suburban district told me that the one thing I could do to assist his judging was to begin succinctly by telling him what was before the court, remind him of the nature of the case, and tell him what action I wanted the court to take and why I thought I had the right to that action. Once I did this for him, he would be ready to listen to my argument. This particular judge told me that he has so many cases that he can’t read the motions before the hearing, and if he has read them, it was so long ago that he couldn’t recall what he’d read. He has no legal assistant to write memos for him; he does his own legal research, and if you cited more than 10 cases for him to read, he couldn’t do it. He likes being a judge and wants to do the best job he can, but he is forced to come into hearings and trials cold. So, help him be the good judge he wants to be and the quality of his decisions will be your reward.